Discover Your Oven

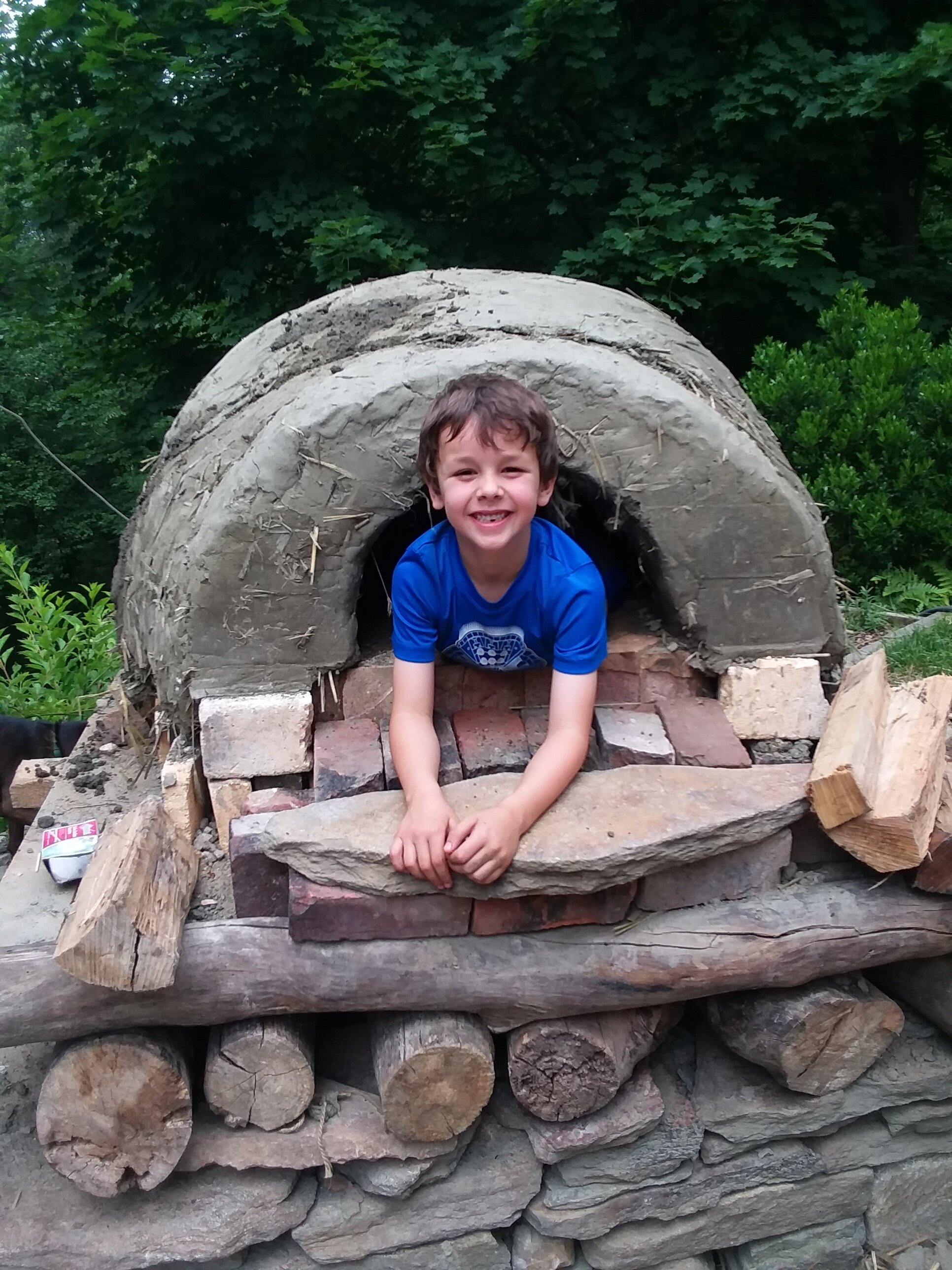

Clay (or cob or adobe) Ovens

People have been building their own ovens from local clay and stone for thousands of years. You can join that tradition.

We source materials locally and we use what you have. Your hands shape the oven that will feed you and your community for years to come.

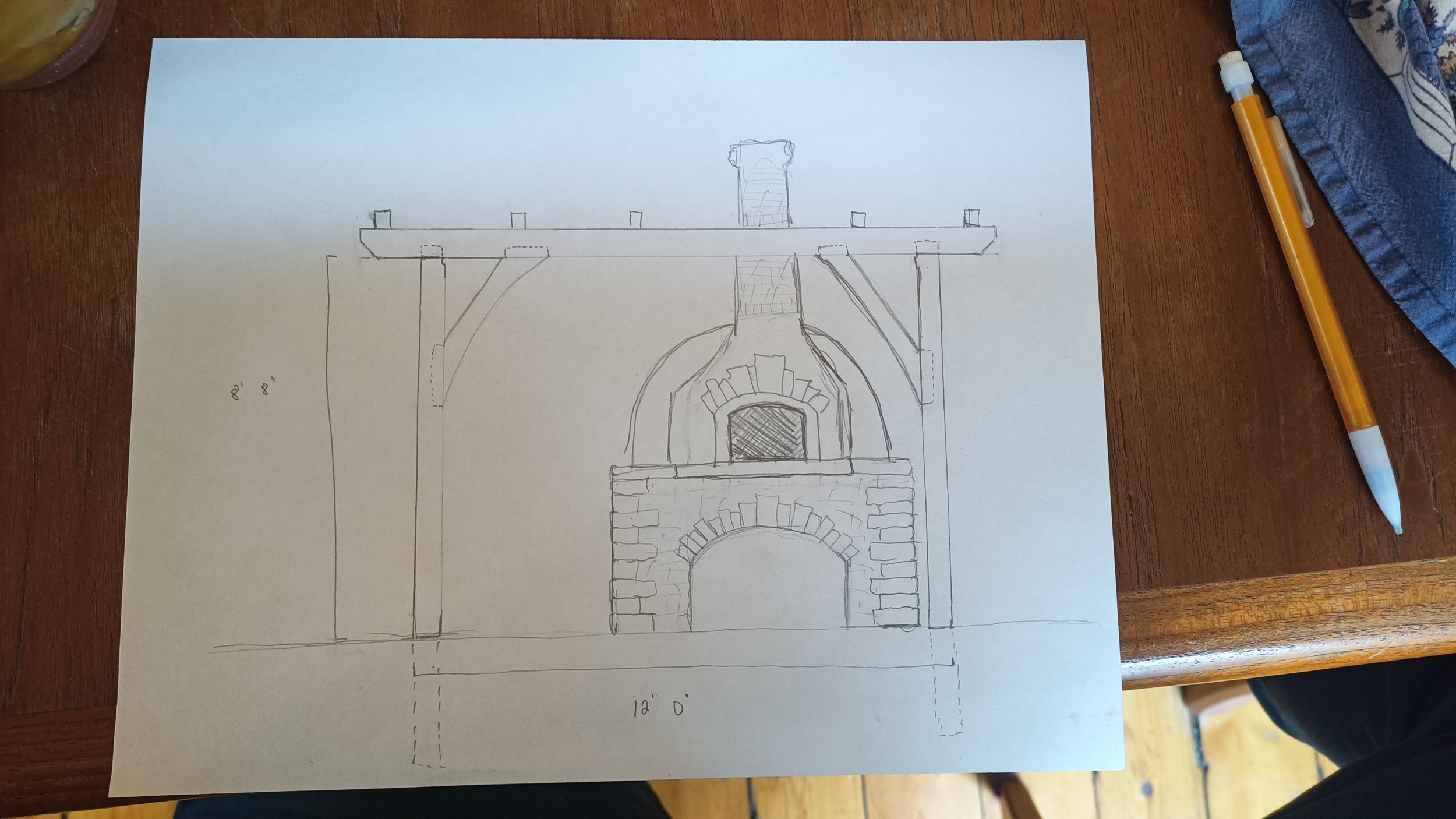

Brick (Masonry) Ovens

We continue the tradition of crafting very efficient bricks ovens. We strive for the highest levels of function and beauty.

You probably have many questions.

Clay or brick? What size? Where should it go? How much does any of this cost?

Email sam@backyardbread.com to schedule a phone call.

Learn more about the clay and brick building process by reading profiles of two oven builds below.

The clay, the stone, and the much of the wood used came from the site. The mud we built with is the same mud that grows her grapes.

The steep hillside above the oven had been terraced with dry-stacked limestone walls. Where the walls had collapsed and spilled their stones down the slope, we pushed them the rest of the way and built our base from that stone. No power saws, just hammers.

Katie picked through a pile of old beams to span the stone base. Even as the stones settle and heave a little on the clay soil, this wooden “table top” will stay rigid and keep the oven above it safe. Generous insulation on top of the wood keeps it from burning.

The bottles, laid on their sides, trap air between the hot hearth bricks and the wooden base. The bottles are bedded in volcanic rock, available in sacks at the building supply stores in France (often used to aerate garden soil). Both the volcanic rock and the bottles trap air, which insulates the wood from the heat and traps heat in the oven. Although not nearly as efficient as industrial, refractory insulators, this method is cheap (or free) and besides, Katie got to pick out her natural winemakers and embed them in her oven.

One of the only other purchased materials were firebricks. Denser than standard red bricks and more tolerant to swings of hot and cold, the bread and pizza and veggies and meat will bake right on top of these bricks.

We dug the clay subsoil from the bank just 10 meters from the oven. The mud was the perfect mix of clay and limestone impurities (sand/pebbles/grog), and could be built with straight out of the ground. Oven mud needs to be sticky enough to be strong but having enough impurities so that it doesn’t shrink too much when it dries, leave big cracks. We formed the mud into little “bricks” and then laid them on a sapling frame.

Looking up to the top of the dome, right before the "keyhole" gets filled in. During the first fire of the oven, the clay will harden and the saplings form will burn out, leaving grooves in the fired clay.

One of the few high-tech materials we use (as an option) is ceramic fiber blanket. This insulation is made by spinning and ceramic into threads, which are then woven into a relatively dense blanket material that is an incredible insulator and can withstand very high temperature. This blanket will make the oven much more efficient, easy to use, and enjoyable over its lifetime, and the blanket can be resused when the oven gets broken down and rebuilt years from now.

For the two weeks of our oven build, we would watch the cows wandering the other side of the valley and hear their bells echo towards us. At the final step of the oven, it was finally time to meet them. We collected six buckets of very green manure (both in smell and in color). These cows only eat grass and the grass and the cows are famous in this region for, among other things, the comte cheese they contribute to. The manure is mixed with clay to create the final plaster on the oven.

With the exception of the desert, clay ovens need roofs or they will simply get washed and worn away. They are, after all, earth. This shed roof was built from mostly new materials from the lumber yard. The braces, however, were old locust grape trellis posts with the rotten ends cut off to leave perfectly strong, beautiful wood. Those posts were found, of course, leaned up against a limestone retaining wall a hundred meters from the oven.

Given enough time at the end of an oven build, one can add final touches. Pam Yung, who organized this oven build, brought these shells from Spain with the intention of putting them in the oven.

A few slow fires dries out the oven and slowly fires the clay. The fire is built in the front of the oven because the inside is so humid. As coals are created and the fire is more robust, one can push the fire into the wet oven without it getting extinguished.

Wood-fired, Montreal style bagels with the warmed-up Mont D’Or cheese (a regional specialty, I was told). And wine, of course.

This is what SongSoo said to me when I told me when I told her how much I loved the cabbage she roasted during our inaugural oven party. She added, later, “Cabbage is delicious gently loved too, just FYI.”

Photo taken by SongSoo

Local stone, red brick, and lime plaster define this dome oven. We built this oven for a serious home-baker with aspirations of teaching classes and selling on a microbakery scale.

This 11’ by 11’ floating slab would serve as both the foundation for the oven, the foundation of the shed roof, and the working surface for the baker. A little more concrete makes a clean, flat working surface. Under the slab is two feet of crushed stone for drainage.

This brick barrel vault springs off of two walls of solid stone and lime mortar, and this forms the base of the oven. The oven floor will be on top of the bricks pictured above. We have the pleasure, when building these ovens, of using traditional methods and materials (lime mortar, barrel vaults, “structural stonework” as opposed to “veneer stonework”), which are rarely used today. The result is beautiful, interesting, and just as cost effective as the standard base built out of cinder block and then treated with some kind of veneer.

This space under the oven could be used for storage or for kindling. But our favorite option is that it be used as dog house for the baker’s best friend…..

This is the floor of the oven. This is the surface on which all the bread will be baked, all the pizza turned, and all the chicken roasted. This is the hearth. Underneath the hearth is a four inch layer of Foamglas, which is a puffed glass product which insulates the hearth. We use very high quality insulation, and a lot of it, so the heat from the wood fire stays in the oven as long as possible.

When we build dome ovens (as opposed to barrel vault ovens), we cut each brick in the shop and number them. Then we bring them to the build site and can, in two days, mortar the dome together.

The last few bricks are cut on site to match the exact hole. These keystone bricks lock in the dome and complete the infinite number of arches that form up the dome. Some ovens are built as domes and some as vaults. A dome like this is virtually impenetrable; as the bricks heat up and transfer ever more pressure along the curve, that pressure just goes right into the floor of the oven.

The chimney on our brick ovens is at the front of the oven. This way, a door can be put on the mouth of the oven and no heat will escape up the chimney. You will notice that our clay ovens usually don’t have chimneys; this is just to simplify the build. Once the base of the chimney is built, the rest of the chimney can be metal, brick, or plastered.

We insulate with ceramic fiber blanket, a refractory material used in blast furnaces and kilns. It’s incredibly efficient at preventing heat from leaving oven. When a baker pulls all the fire out of the oven, they rely on the retained heat in the brick to bake their bread, veggies, meat, etc. The heat cannot leave the bricks and go through the ceramic fiber, so instead it just keeps dumping its heat back into the baking chamber and into our food.

We use naturally hydraulic lime for our mortar and our plaster, which can be tinted with mineral pigments. The counters are both an aesthetic choice and a functional one.